Since inception, pregnantish’s mission has been to amplify untold stories of infertility and reproductive health. Pregnantish often asks: who is left out? And then fills in the gaps through research and storytelling.

Recently, pregnantish published an article providing an update on trends in Asian infertility from a global perspective. This was inspired by the success of our first capture of Asian infertility in 2018, written by Seattle journalist and infertility advocate Annie Kuo, which has trended on Google ever since (clearly there is a need for more good work like what Annie wrote for pregnantish!).

With support from Generation Next Fertility, this next piece aims to serve as a continuation of the conversation, and a deeper dive into the lived experiences of those most impacted by the policies and trends found in Asian communities with infertility.

Research from UCLA Health and others demonstrates that Asian Americans are 50% less likely than other racial groups to seek mental health services. In some Asian cultures, talking about mental health challenges is not encouraged, or can be perceived as weakness. Studies cite how the stigmatization of mental health acts as a barrier to care, which can create a domino effect that discourages Asian patients from seeking care for other health concerns as well, including infertility.

Racial Inequities in Infertility

There are not enough studies out there that look at the intersection of infertility and race. What does exist points to upsettingly common trends of racial and class inequities in healthcare that deserve much more attention than they’ve been given.

Of the scientifically published articles that exist, trends showcase that Asian patients have greater difficulty conceiving, wait longer to seek infertility treatment, and experience decreased treatment success rates than their white counterparts.

Of the scientifically published articles that exist, trends showcase that Asian patients have greater difficulty conceiving, wait longer to seek infertility treatment, and experience decreased treatment success rates than their white counterparts. Several studies cite cultural factors as barriers to accessing treatment, as well as genetic and possible environmental predisposition.

Existing literature and studies pulled from the CDC and SART databases demonstrate that Asian patients undergoing fertility treatment differed from white patients in a few key characteristics:

- The age at which they sought treatment is higher

- Asian women are more likely to have never been pregnant before (58.9% vs 52.9%)

- Those of Asian descent are more often given the diagnosis for diminished ovarian reserve (11.4% vs. 7.9%)

- Asian patients experience higher rates of endometriosis (15.7% vs. 5.8%)

Unsurprisingly, these differentiators have translated to poorer outcomes, including:

- Decreased live birth rates, even after receiving treatment

- Increased rates of stillbirth

- Increased fetal loss across all gestational ages

But where is this differentiation coming from?

Though some studies solely cite genetics, it is clear that there is also a social and cultural dynamic at play that is delaying Asian patients to seek treatment and therefore decreasing their chances of success in treatment.

Studies using CDC data showed that Asian women demonstrated higher reports of psychosocial pressure to bear children, and blame for an inability to conceive.

Asian women are more likely to report that their providers did not understand their backgrounds, nor involve them in healthcare decisions as much as they’d wanted. These factors can jeopardize the patient-provider relationship, affect clinical outcomes, and ultimately turn patients away from seeking the care that they need.

Annie’s Update: Six Years Later

We had the honor of reconnecting with Annie to learn more about her story and passion for better representation, and access to care:

“After a second trimester pregnancy loss, I was diagnosed with diminished ovarian reserve in my mid-30s. It was a bewildering experience to lose a pregnancy and then not know why I wasn’t getting pregnant for another year following that. I didn’t know anyone my age who had miscarried, and when I shared the loss with people, their comments were often dismissive, judgmental or critical. I felt misunderstood and ashamed. Even my mother, who’d had 3 kids before she turned 36, asked me what was wrong with me because nothing like this had ever happened to her. Ironically, I later found out that her early menopause (before age 51) and osteoporosis are linked to hormones that I inherited. I just started in earnest to build a family at an age where she already birthed all the kids she wanted. We never talked about her early menopause in our household, nor did I know that was an inheritable trait that would affect my fertility window for conception and maintaining a pregnancy.

I went to Washington, DC to advocate for family-building legislation following several unsuccessful attempts at fertility treatment to preserve the chance to have another child. I noticed there were very few Asian Americans among the advocates and even fewer in the RESOLVE support groups that I would host over the next five years. I began to wonder if there was a cultural dynamic between what I had experienced personally and what I was observing in the community.

Besides my friend Maya Grobel, a biracial woman whose infertility story plays out on the Netflix documentary One More Shot, I seemed to be the only other Asian American fertility patient at the time who was speaking up on a national level about the experience of infertility. I was featured on NBC Asian America, but there was so much more I was finding out on my own that I wanted to share with the community. [Pregnantish Founder] Andrea Syrtash and I knew each other from advocacy trips to the nation’s capitol to advocate for family-building legislation. The stars must have aligned in terms of my interests and the opportunity because she asked me to write about the topic.

Access to care for Asian communities is important to me because it’s an equity and social justice issue that addresses people’s ability to find appropriate support for their conditions no matter what their background is.

Access to care for Asian communities is important to me because it’s an equity and social justice issue that addresses people’s ability to find appropriate support for their conditions no matter what their background is. Access to care means that anyone who wants to build a family will be able to achieve that dream if they can get timely help and are not limited by the ability to pay. Similar to what’s happened with the Black civil rights movement influencing progress for other communities of color, I like to think that the spotlight in recent years on Black infertility, for example in Oprah Magazine, will help other people of color to examine the cultural expectations and biological differences we might ourselves have when it comes to building our families and seeking support, medical and social, when we have trouble.”

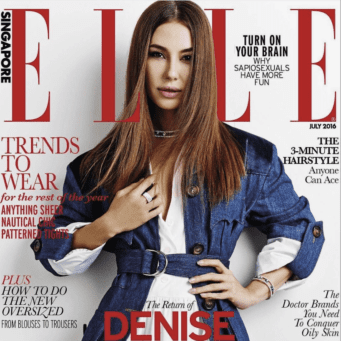

Asian Global Stars Chime In: Denise Keller and Juri Watanabe

Pregnantish had the privilege of connecting with two major global leaders to help us smash taboos in the Asian community: former MTV Asia VJ and Discovery Channel TV presenter and producer, Denise Keller and Miss Universe Japan 2021 and actor, Juri Watanabe.

Denise is a Singaporean model, TV presenter and producer, of Chinese and German ancestry. Denise is an extraordinary example of why representation matters – she strives to elevate the conversation about issues like infertility, pregnancy loss, and motherhood.

Denise, who has been an avid follower of pregnantish in Asia for years, shares her story:

“I had gone through the whole mental health struggles of feeling like a complete failure that I couldn’t keep a pregnancy or I wasn’t getting pregnant. And I just knew that I was never going to be a mother. And that was my only wish – to have a child after being on the road for 20 years. That’s what I really wanted. And nobody would sit down and have that conversation with me. So, I would have to say (the experience) was a massive roller-coaster ride. And in Asia, there are small little pockets of support, though I really feel it could improve more. There is a taboo of talking about your infertility in Asia. People don’t talk about it casually. You can’t tell somebody that, ‘I’m seeing a fertility specialist’.

In Asia, there are small little pockets of support, though I really feel it could improve more.

Also, (my experience) in Asia, especially if you’re a public figure, you don’t want to give too much information…

I found a group of women in Singapore who did a bit of the Chinese whispers ‘Oh, are you struggling?’ ‘Yes, I’m struggling, too.’ And we started talking and sharing sources of information with community groups. And I started building more upon it. And that gave me the strength and also the empowerment to vocalize more about it.”

Juri is a model, actor and activist of Japanese and Korean descent. Juri uses her platform so that others who are struggling, both in Asian culture and outside of it, feel less isolated around issues like mental health struggles. She shares:

“A lot of the work I do is really about bridging the gap between the East and the West. So when I came back to LA, (I’ve wanted to) represent Asia in the best way possible and also help the Asian community de-stigmatize areas like mental health. I think that’s an area that the West does really well. I feel that by being this cultural bridge, we can all learn from each other.

A lot of the work I do is about bridging the gap between the East and the West. So when I came back to LA, (I’ve wanted to) represent Asia in the best way possible and also help the Asian community de-stigmatize areas like mental health. I think that’s an area that the West does really well.

There’s just a huge pressure of women choosing either career or family…When I was interviewing for a job, some of the common questions that I would be getting was, ‘are you planning? Do you have a boyfriend? Are you planning on getting married?’

There’s still this social expectation that women choose family and build a family over career or you just go full on with a career, you have to give it your all. And then by the time a lot of the women that I speak to want to start a family, sometimes it’s a little bit too late, but they don’t have the resources or information on the egg freezing process or to know how to start…”

Doctors Weigh In On Improving Care for Asian Patients

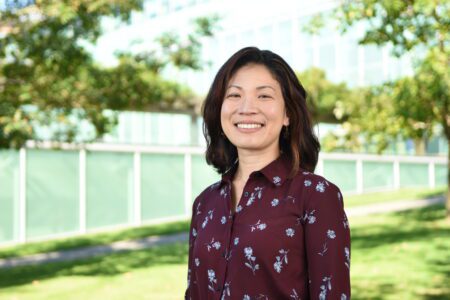

Dr. Julie Lamb is a board-certified reproductive endocrinologist practicing at Pacific Northwest Fertility in Seattle and Bellevue and serves as clinical faculty at the University of Washington. Dr. Lamb has been published for her research on Fertility Characteristics and IUI Outcome Associated with Asian Ethnicity.

Dr. Lamb shares, “I trained in San Francisco and now work in Seattle – there is a large population of Asian patients in both cities so I spend a lot of time thinking about how to give them the best possible success rates. Asian infertility treatment differences were a big topic when I was in fellowship, and we continue to use data from research papers in considering how to best treat our Asian patients. This topic has been a big part of my patient care – from fellowship to my practice for the last 15 years. I’d say 40-50% of my practice [identifies as] Asian. It’s important to take a step back and pay attention to what we can do to give the [Asian] population the best opportunity for success.

I’ve definitely seen stigma [affect] my Asian patients. Patients will tell me, ‘my family really wants me to pursue this and have a baby.’ There can be a lot of family pressure in this population, and hesitancy about sharing details of their situation.

We definitely need more research. There has been some more demographics in case reporting but not much on what can be done to improve outcomes. For example, Asian patients likely metabolize estrogen differently – how does that impact implantation and pregnancy rates?

We definitely need more research. There has been some more demographics in case reporting but not much on what can be done to improve outcomes. For example, Asian patients likely metabolize estrogen differently – how does that impact implantation and pregnancy rates? High estrogen levels may not be as conducive for implantation [of embryos]. Now we’re seeing more of a role of PGTA genetic testing, and a movement towards frozen embryos for all patients and especially for Asian patients this seems to increase chances at better outcomes.

Moving forward, we are always looking for ways to optimize success rates for Asian patients, and patients across all ethnicities. More studies looking at specific protocols to benefit this population are needed.

I want patients to know that doctors really care about this! We want the best outcomes for our patients, no matter their race or ethnicity. And we are always looking for ways to improve access to care and improve outcomes.”

Dr. Janelle Luk is the Medical Director and Co-Founder at Generation Next Fertility. We are grateful for her leadership in sharing her experiences as an Asian American, Reproductive Endocrinologist, and Infertility Specialist.

“As I grew up, I felt passionately about women’s health and wanted to [become] an OBGYN. I didn’t know specifically about infertility, but [definitely] women’s health. I still remember when I first understood the [translated] Chinese words – they explained the vagina is the ‘dark path.’ It sounds bad! And then menstruation is something that I still remember you couldn’t talk too much about in school.

When I was in college, I was one of the sexual health advocates on campus. And I still remember no one really wanted to talk about it… I was also the only Asian educator. I’m extremely passionate… As a sex health educator I was promoting lots of those messages and making sure people were empowered and understood protection.

In that culture of not really celebrating women’s bodies, in a culture where fertility is part of your job, or [it’s common to] degrade certain parts of the body… It is hard to find a woman herself to say, ‘I’m so proud of being a woman.”

Dr. Luk has committed her life and career to helping women like her to reclaim their bodily autonomy and empowerment.

I want to take care of women who are younger, who [for example] have endometriosis, and help them understand what that is… Women of all races should be treated with enlightenment and empowerment.

“[Research shows] that IVF medications sometimes have different effects on certain women, such as Asian women. Some studies have demonstrated that the Asian woman’s receptors may require more FSH for a certain response… We have seen that collectively, [Asian women] may need more medication for stimulation. PCOS in Asian women is also different in PCOS a Caucasian or African American women. So, the same disease – infertility – does not demonstrate the same expression and symptoms in every across all races.

I want to take care of women who are younger, who [for example] have endometriosis, and help them understand what that is… Women of all races should be treated with enlightenment and empowerment.”

What’s Next? Pregnantish: Asian Infertility Part 3

Our upcoming podcast episode, the final segment in our three-part series on Asian infertility, focuses on the importance of breaking stigmas for improved clinical outcomes and expanded access to care. Tune in to hear pregnantish Founder Andrea Syrtash connect live with Denise, Juri, and Dr. Luk about their lived experiences of infertility and mental health as Asian women and leaders in their fields.

Pregnantish is dedicated to our “Real Talk About Fertility” mission to amplify under-told conversations about the nuanced lived experiences of infertility. We hope that through this series, more people of Asian descent will be able to access the support, resources, and care they deserve.

This article is supported by Generation Next Fertility in New York City, whose mission is to provide individualized patient centric quality care and innovative technologies to help patients become parents. For more, visit generationnextfertility.com