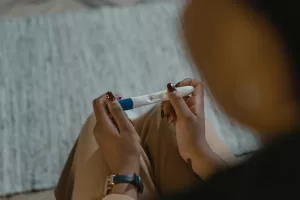

Singapore’s Ministry of Health recently made amendments to regulations concerning assisted reproduction services, effectively prohibiting elective sperm freezing without a medical indication

This decision sets Singapore apart from other developed countries, as it is the only nation currently banning sperm freezing.

The Ministry’s rationale for the ban is rooted in the lack of sufficient evidence indicating a significant decline in male fertility after a certain age. Consequently, they argue that the service is unnecessary.

At first glance, this ban may appear to be biased against men, especially when considering that Singapore recently allowed elective egg freezing for women between the ages of 21 and 37, irrespective of marital status. Unlike elective egg freezing, collecting sperm for freezing does not involve medical interventions or surgical procedures, making it relatively safe and more affordable. Therefore, some argue that the ban seems unjustified, considering that scientific evidence suggests a gradual, non-drastic decline in male fertility and sperm quality with age.

However, a closer examination reveals that the ban on elective sperm freezing is a justifiable and prudent step taken by the Singapore Ministry of Health to protect consumer rights and prevent the exploitative marketing of unnecessary medical services by local fertility clinics.

Singapore’s socio-cultural context creates an environment where the population is particularly susceptible to the exploitative marketing tactics of local fertility clinics, promoting wasteful elective sperm freezing services.

Firstly, Singapore’s predominantly Chinese culture is influenced by traditional beliefs rooted in Taoist philosophy, which espouse that younger men possess stronger “Qi” (life force) and “Yang” (male energy), enabling them to father healthier and more intelligent offspring. Consequently, there is a fear that older sperm may result in lower quality offspring. This fear motivates many younger men to freeze their sperm, ensuring the possibility of conceiving higher quality children after marriage.

However, it is crucial to question the necessity of this practice, especially considering that the vast majority of men typically complete their family formation by their mid- to late-forties.

Men who freeze their sperm at a young age may be tempted to undergo in vitro fertilization (IVF) with their frozen samples, even if neither partner has fertility issues, under the belief that it will yield higher quality offspring. Subjecting healthy and fertile individuals to IVF for such unfounded reasons would be considered clinical malpractice.

Secondly, Singapore has experienced persistently low fertility rates in recent years, with the total fertility rate (TFR) hitting a record low of 1.05 in 2022. This means that, on average, married couples in Singapore will only have one child. Consequently, many men feel compelled to invest heavily in their future single child, including undergoing elective sperm freezing to ensure the possibility of conceiving a higher quality offspring.

Thirdly, Singapore has implemented mandatory military conscription, known as National Service, for all able-bodied males since 1967. While rare, local news media have reported accidental deaths and injuries during peacetime military training, causing significant fear and anxiety among conscripts and their parents. Promoting elective sperm freezing for military conscripts, funded by their parents, could assuage these fears and anxieties.

Lastly, based on Confucian social norms, Singapore’s predominantly Chinese culture places great emphasis on continuing the family lineage through the male line as an act of filial piety towards one’s parents and ancestors. This cultural aspect may encourage individuals to opt for elective sperm freezing as a form of “fertility insurance” to guarantee the continuation of their family lineage. Parents or grandparents, recognizing the risks associated with military conscription in Singapore, may willingly sponsor this practice, particularly when the conscript is the only child in the family.

However, if a conscript were to pass away during service, the issue of posthumous reproduction and the use of foreign surrogates (which is banned in Singapore) would arise. Posthumous reproduction is widely considered unethical and is banned in many jurisdictions, as it intentionally denies a child the presence of a parent even before birth.

Additionally, elective sperm freezing could pose long-term security risks. Aggressive sales pitches and advertising campaigns may exploit fears of dying during national service. However, it is important to note that over the past 20 years, only 42 national servicemen in Singapore have died while in service, averaging about two deaths per year. In contrast, the annual death toll from traffic accidents in Singapore typically exceeds 100. Consequently, promoting elective sperm freezing for military conscripts is entirely unwarranted and unnecessary.

Nevertheless, both domestic and foreign fertility clinics may take advantage of service-related deaths to aggressively market elective sperm freezing to Singaporean patients, potentially creating negative public perceptions of conscription, which is a crucial aspect of Singapore’s national security.

Therefore, without a ban, local fertility clinics are likely to launch aggressive advertising campaigns to encourage the unnecessary uptake of elective sperm freezing, exploiting the socio-cultural vulnerabilities present in Singaporean society.

Related content:

Singaporean women will be able to freeze their eggs for non-medical reasons