After presenting Woman’s Hour last month, Emma Barnett found herself drawn to a government website after an emotional interview regarding the government’s new baby loss certificates, prompted by Zoe Clark-Coates, founder of the baby loss charity, Mariposa Trust. Zoe’s advocacy, born from her own painful experiences, resonated deeply with her.

During the conversation, the realization struck her – she too could apply for this certificate, marking her as part of the first wave of women in England to do so. Without much hesitation, she decided to proceed, involving her husband in the decision-making process to ensure his comfort with it.

The application process, though straightforward, stirred unexpected emotions. Questions about the timing of her loss brought her face to face with the blurred edges of her grief, as the memories of January 2022 – when she lost her baby after a taxing journey of five rounds of IVF – felt distant and yet painfully vivid.

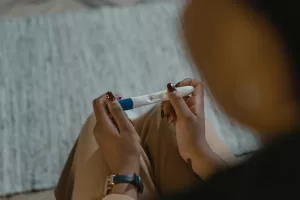

“I was alone when I found out – not something I recommend if you can help it. I hadn’t been feeling quite right for a few days and wanted some reassurance. So I booked a private scan, to the tune of £120, to put my mind at ease. My husband had offered to come but it was tricky with his work that day, so I told him not to worry, I would do it alone.

“That turned out to be a big mistake. I stumbled out of the clinic, into the harsh sunlight of a busy London road, knowing that our dream was over. Gone.”

Despite the well-meaning encouragement to move forward, she found herself unwilling to let go. The bond she had formed with her baby, though intangible to others, was palpable to her. Like countless women before her, she carried the weight of her loss within her, with only her body and mind as witnesses to the brief but profound existence of her child.

For many, the idea of possessing a formal document may seem unnecessary. However, the realization dawned on her during her conversation with Zoe that having official recognition of their loss could serve as a significant addition to their family narrative. Their experience, she felt, deserved acknowledgment within the folds of official paperwork.

Reflecting on history, she recognized the glaring absence of women and their stories from many records, their lives often relegated to mere footnotes. Applying for the baby loss certificate felt almost like a political act to her, a refusal to allow such a pivotal moment in their family’s life to be erased and forgotten.

When the certificate finally arrived, neatly encased in its official government envelope, she experienced an odd sense of satisfaction, a validation of their experience. It stood as tangible evidence, an external testament to their journey, which her husband and future children could one day acknowledge as part of their shared story.

While acknowledging that the certificates may not resonate with everyone, she believed they could facilitate a deeper understanding of grief for others, offering an official marker to commemorate the significance of a pregnancy and its loss.

Recognizing the anticipated demand, she understood the temporary limitations imposed by the government to prevent overwhelming the system. However, she remained hopeful that in time, the certificates would become accessible to all, allowing countless women to honor losses from years past.

Filing their certificate alongside the birth records of their other children, she acknowledged its potential to become a quiet source of reflection in moments of solitude. Though the grief existed independently of any paperwork, she found solace in knowing that their experience was now documented, a testament to the profound journey they had traversed.